Recently, the Lewis-Houghton and the Civics and Democracy Initiative has had me thinking about music and its role in the classroom. The Initiative, launched in 2023, strives to inform how the music and arts have contributed to American democracy. As a consumer, creator, and appreciator, music holds an omnipresent place in my day to day.

Even as an English teacher, I would frequently include music as a part of my regular curriculum throughout the year. I would use lyrics from my favorite tunes in my grammar lessons, pull examples of figurative language from pop songs, and obnoxiously belt the “Beasts of England” when reading the first chapter of Animal Farm. Language is inherently melodic- it holds a cadence that, when commanded well, is infinitely influential. It always felt natural that it held its place alongside literature.

Yet, in all my recollections, I cannot remember a single history class opening with a song. When we learned about the Revolutionary war, I never learned what anthems the British soldiers sang before fighting and dying for their country. I never knew what songs the lumberjacks bellowed in their mess halls after the work that would influence the growth of my home state. Never once did I actually hear a single piece of music that arose from the Harlem Renaissance in the classroom, despite being taught about it nearly every year.

The reasons for this may be endless. Limited time, limited access, and perhaps greatest of all, limited interest. Why might a student care more about an archaic tune than the Bill of Rights? Case in point being that I never sought out these songs of my own volition. Yet, oddly enough, some of these tunes managed to find their way into my ears anyway.

My exploration on this idea began when I came across this rendition of “Black Betty,” recorded by the Lomax family in 1939. John A. Lomax, with his wife, Ruby, and son, Alan, travelled the country in the pursuit of collecting the local folk tunes that threatened to be lost to time. They captured hundreds of tunes along with information about those that sang them in the Archive of American Folk-Song.

The name of this item is what drew me, as it reminded me of a song by the same name recorded by Ram Jam in 1977. But the melody and lyrics are truly what captured my attention. The tune of the song is nearly identical to this modern rendition, and the lyrics, despite changing slightly, remain largely the same.

Sung by Moses “Clear Rock” Platt at the Hotel Blazlimar, the bibliographic information records "Black Betty" as a “tree-cutting song” that one might sing while working. The first verse of lyrics, which are absent in most modern interpretations, seem to support this:

"Oh, Black Betty, Bam-ba-lam

Oh, Black Betty, Bam-ba-lam

Black Betty’s in the bottom, Bam-ba-lam

Black Betty’s in the bottom, Bam-ba-lam

Just hewing on the timber, Bam-ba-lam

Just hewing on the timber, Bam-ba-lam"

If one thinks of the song as a “communal piece” sung during a work-day, one can imagine the call and response nature of the song as it is presented above. The next verse, prompted by who we can likely assuming to be Lomax, is sung as follows:

“Black Betty had a baby, Bam-ba-lam

Well, the thing went crazy, Bam-ba-lam

Just drinking river water, Bam-ba-lam

Oh, Black Betty, Bam-ba-lam

Oh, Black Betty, Bam-ba-lam"

It isn't until this verse that the familiar lyrics of the song by Ram Jam emerge, with some slight variations. However, the "tree-cutting" aspects of the lyrics are lost in their entirety- in fact, this verse appears to have almost nothing to do with the verse that precedes it. These discrepancy provides an opportunity to look at this song critically and begin to ask some questions:

- Why might entire verses appear in the folk version that are not the modern interpretation?

- Why might verses that do appear have different lyrics than they do in a modern interpretation?

- What do the lyrics in the song mean? Who/what might “Black Betty” refer to? Does the meaning of the song change as it is adapted?

- What might the original song tell us about the people that sang it? What does the adapted song tell us about the people that sang it? Do these two different groups have a similar focus?

- What emotions are evoked by the tempo/tone/lyrics of the original song? Are these same emotions evoked in the modern adaptation?

These last questions even force historical inquiry – who was the person that sang this song?

Lomax, Alan, photographer. Moses Platt Clear Rock Sugar Land, Texas . Sugar Land Texas United States, 1934. June. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2007660011/.

Thanks to the Lomaxs’ collection of field notes taken during their gathering of folk music and complimentary notes provided on the Lomax Digital Archive, supposed information about Platt is readily available. Platt was a man who had spent nearly his entire life in Texas prisons, the nickname “Clear Rock” being given to him due to claims that he had killed three people by throwing rocks at them. He was a self-described “habitual” who seemed to find himself behind bars more often than not. Yet, he was beloved enough to rally the support of his local community to a degree that caught the Governor’s attention and earn himself a pardon. After this point, he went by “The Reverend Mose Platt,” and sang mostly hymnal tunes "for the entertainment of his white friends." His story provides context but creates just as many questions, as it paints the picture of a man who is awash with contradiction.

This song led me to look for pieces of a similar theme, where a more modern version of a well-known melody exists as an adaptation of something much older. There are quite a few examples - one that stuck out was “Cotton-Eyed Joe,” sung by Elmo (or possibly Earl) Newcomer and recorded at his ranch home in 1939. This singer, too, has more information to explore through the Lomax field notes.

This song today is much more well-known from the 1994 rendition by the Rednex, which is played at nearly every high school dance in rural Illinois. Likely danced to in the same way it was danced to a century ago. In their notes they claim that Newcomer "..has 'always' played these tunes and is a favorite caller at dances." But who or what does "Cotton-Eyed Joe" actually refer to? Did Newcomer know? Why is this a song that has persisted across decades? This piece can be examined using many of the same questions that were asked above.

It should be prefaced, however, that in several of these "classic" renditions of the songs, some lyrics that differ contain language that rightly does not persist in modern renditions due to its racist or derogatory nature. The context of these songs, in combination with their singers, should be taken into account when dissecting their meaning and importance. They reflect the language that was prevalent in these periods, which make them valuable, historical artifacts.

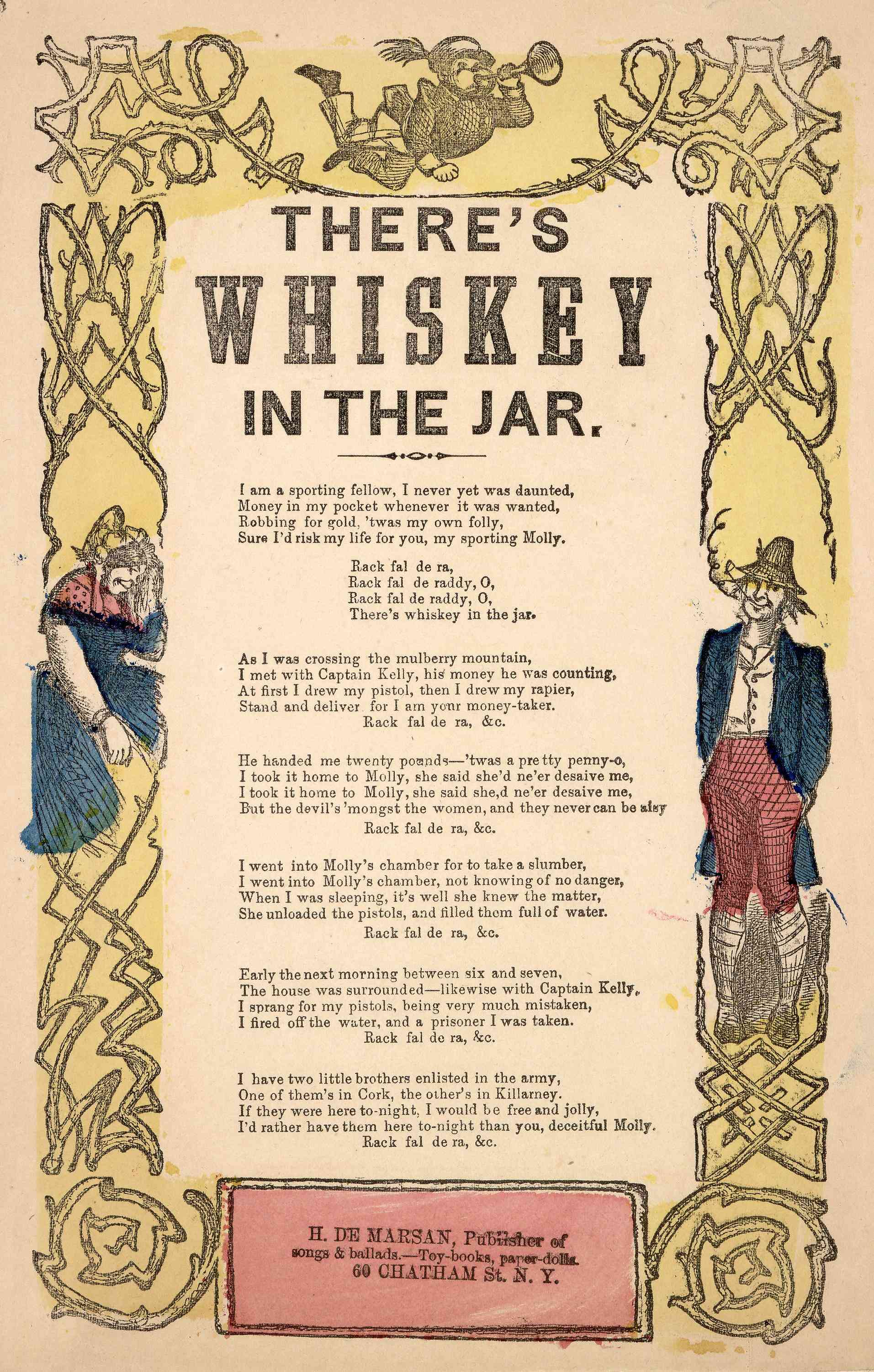

“Whiskey in the Jar,” is another piece which seems to have pervaded across time, popular renditions recorded by Thin Lizzy in 1972, by the Dubliners in 1990, and again by Metallica in 1999. Yet, even these modern versions are still simply adaptations of a much, much older tune!

There's whiskey in the jar. H. De Marsan, Publisher, 60 Chatham Street, N. Y . Image. https://www.loc.gov/item/amss-sb40503b/.

It's entirely possible that learners may not be familiar with all of these pieces, but the idea of familiarity is what is critical. Beginning with music that is familiar is a strategy to get them interested and to begin asking questions about the context of a piece - once learners are effectively able to ask these questions on their own, they can be moved to music that does not have as many easy parallels, both old and new. Even if these classic songs are not familiar, any number of variations of Yankee Doodle can be used to communicate these same ideas. What is a "Yankee Doodle Dandy?" What does it mean to stick a feather in his hat and call it macaroni? Has he always done that, according to alternative versions of the song?

It is easy to forget music in the struggle to teach about history. Rarely does a song provide a bounty of accurate and easily digestible information. However, a song contains what most other accounts can never hope to hold: the true emotion of a moment. In looking at the different renditions of a familiar tune, we might discover the different ways that our ancestors felt in times of trouble. More importantly, we might discover the many ways that we feel the same.