The year is 1839. It’s a somber day in New York as Stephen van Rensselaer is laid to rest. Among the richest men in American history, Rensselaer would be remembered for many things: a man of science, a venerable general, and a devout man of God. But most notably, as referenced in a sermon given following the funeral, Rensselaer would be remembered for his "innumerable rills of refreshing bounty which he caused to circulate among the poor... he was as ostentatious as he was liberal in his benefactions.."

Stephen Van Rensselaer / engraved by G. Parker, from a miniature by C. Fraser . Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/98509983/>.

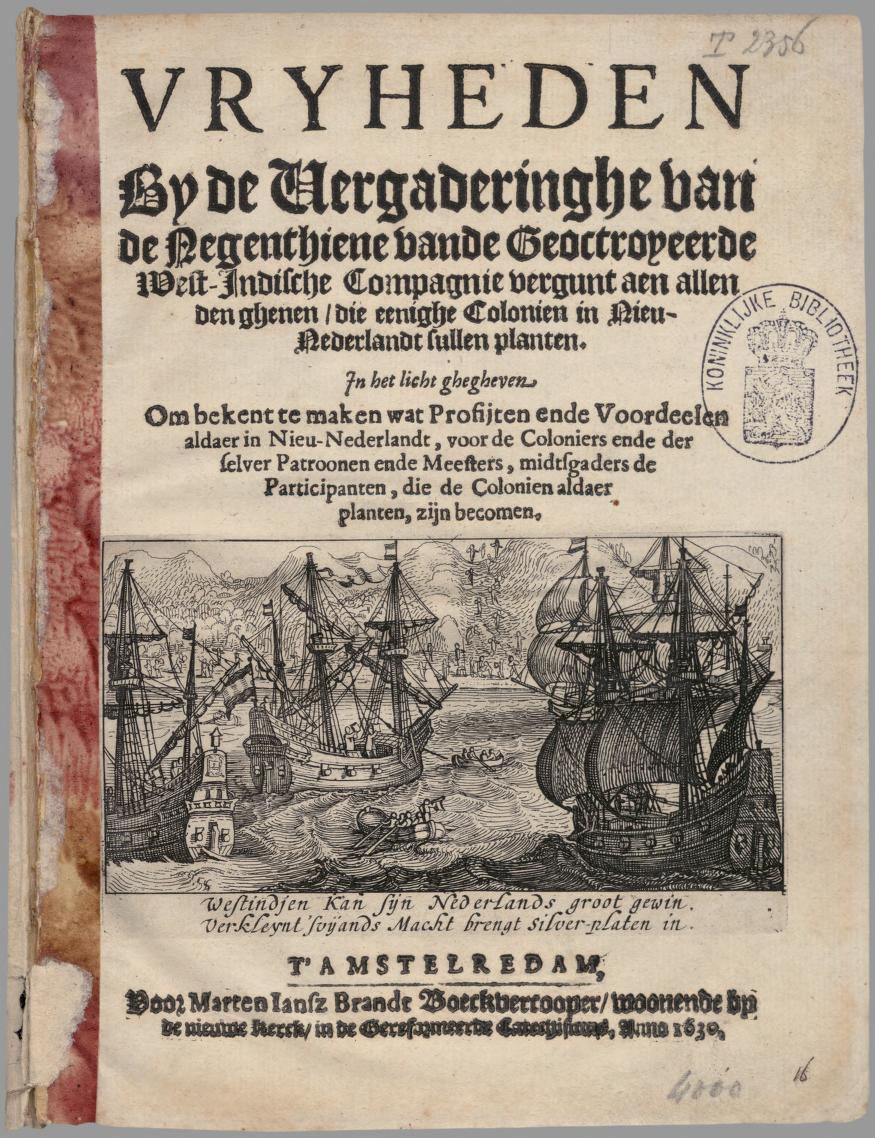

But this was not the only circumstance for mourning in the state of New York. Just two years earlier, the economic panic of 1837 swept the nation, and the country was still strongly held in the recession’s tight grasp. Many of the nation’s banks failed, gold and silver were sparse, and money was even more so. While those wealthy enough, like Rensselaer, were able to avoid the immediate effects, many were not so lucky. Evictions, poverty, and homelessness were rampant throughout the nation, but it was in New York that Rensselaer had offered some reprieve.

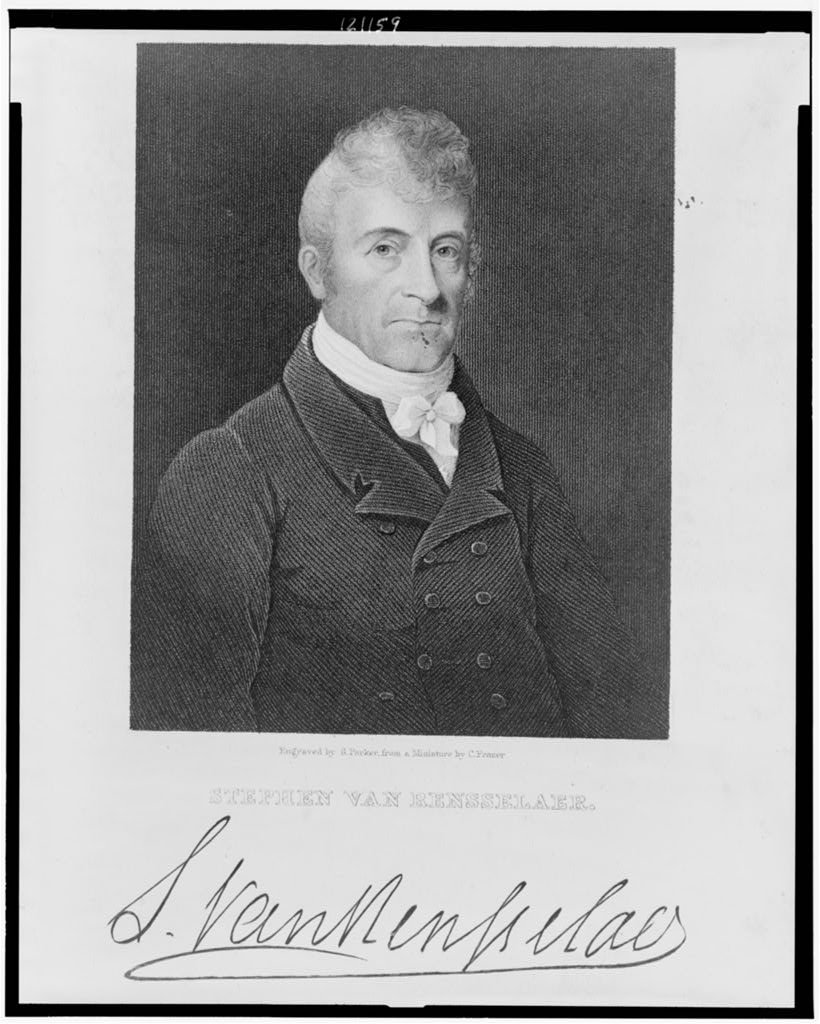

The Rennselaer family were considered “patroons” of the Hudson Valley area, which remained as a facet from Dutch settlement of the area in the late 1600s. What this meant was that Stephen Rensselaer owned a significant amount of land that was provided to individuals in the form of a lifetime lease. In some cases, entire communities were owned by a single individual, the entire town leasing the land on which they lived. In Stephen van Rensselear's case, this equated to 1,200 square miles of property with over 80,000 people living within it.

West-Indische Compagnie Author. Freedoms, as Given by the Council of the Nineteen of the Chartered West India Company to All those who Want to Establish a Colony in New Netherland . Madrid, Spain: Marten Iansz Brant, 1630. Pdf. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2021666730/>.

Though the 1837 panic caused hardship for many, Rennselaer’s position as a patroon actually alleviated struggle families instead of causing them greater distress. Rather than eviction, Rensselaer would forgive late payments in exchange for goods and services, partial payment was accepted in lieu of eviction, and many were able to stay in their homes during the height of the economic collapse. Though the payments may not have been collected, they were not forgotten - the Rensselaer estate still kept track of every penny that was owed.

And so, for many that were indebted, Rensselaer’s death was a ray of hope - perhaps the outstanding balances held by thousands would be laid to rest with the man who had shown them generosity in the course of his life. Perhaps it would be freedom from the economic hardships that plagued the nation - a chance for a new start.

But they would not be so lucky. The Rensselaer Estate, despite its wealth, was also struggling. Years of slow financial decline, culminating the panic of 1837 led to the annihilation of Stephen's fortunes, leaving substantial debts to his estate. In an effort to reclaim the wealth lost during the recession, Rensselaer’s will demanded his heirs to collect outstanding payments from the people that resided on the leased land. But financial woes had not yet vanished. Few had but pennies to repay these demands, and rather than leave, they found themselves trapped. A condition in their lease, which demanded a year’s worth of rent or a quarter of the value of the estate upon its sale, prevented many from willfully leaving, trapping thousands in an untenable situation where they could neither pay nor sell their property and leave.

Enraged, the local farmers/lessees headed up Helderberg Hill (referred to as "hell-of-a-hill"), and refused to pay a single penny towards what they owed until certain concessions were made. Because they had no money, they urged the new landlords to accept the fruits of their labor as equivalent compensation, much as Rensselaer once had. Additionally, they wanted to claim the improvement of value on the properties on which they had lived their lives. The debtors refused both claims. For several years, tensions continued to rise between leaser and lessee until a culmination in 1945 led to this "war's" first real bloodshed.

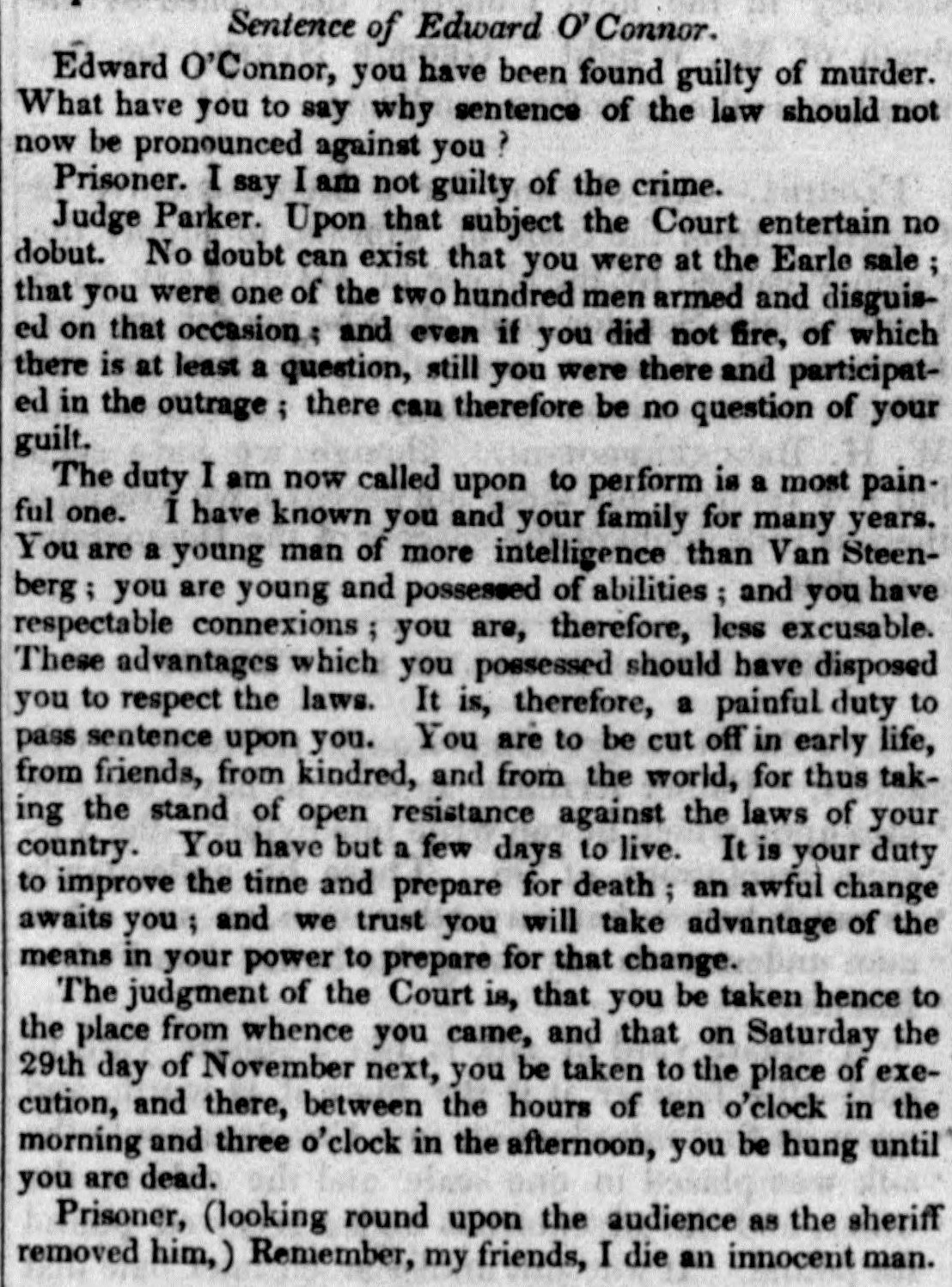

Attempting to collect $64 in arrears, Sheriff Osman N. Steele arrived at the home of Moses Earle, anticipating trouble. If Earle could not pay, it would mean that his property would be sold off in auction, and Earle had made it clear that neither payment nor auction would occur without a fight. Sure enough, moments after arrival, Steele was harassed by a group of individuals disguised as Native Americans who intended to stop any attempt at auction. And stop it they would. After a heated argument, bullets tore into the stomach of Sheriff Steele and he died in Earle's home after several hours of excruciating pain. A firsthand account of the gunfight can be read in an edition of the New York Herald.

Weekly national intelligencer. [volume] (Washington [D.C.]), 18 Oct. 1845. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045784/1845-10-18/ed-1/seq-4/>

Two men involved in the fighting, John Van Steenberg and Edward O'Connor were sentenced to hang for the crime. An edition of the Weekly National Entelligencer gives a partial transcript of the trial where Judge Parker states to O'Connor, "You are to be cut off in early life, from friends, from kindred, and from the world, for thus taking the stand of open resistance against the laws of your country."

It’s a terrible story. From the death of an individual who profited off a broken system, through a community on the brink of economic collapse, to the rise of tensions so great that they led to the death of a man simply trying to uphold the law. There are no "winners."

So why share it?

Because it’s timely.

When having students examine the histories of the past, it’s important to examine it within the context of the present. How are current events informed by or influenced by those events of the past? An apt comparison could be made between the Anti-Rent War of 1839 and the Rent Strike in May of 2020.

-

Cancel the rent rally, Washington, D.C . -07-25. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2023696164/>.

-

Cancel the rent rally, Washington, D.C . -07-25. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2023696163/>.

During this time period, many factors, including the COVID-19 Pandemic, led to a rise in unemployment, a rise in the cost of services and difficulty for many to pay their most basic expenses. And though this strike may not have been as volatile as its predecessor, the sentiments of angry tenants today mirror those of thier ancestors.

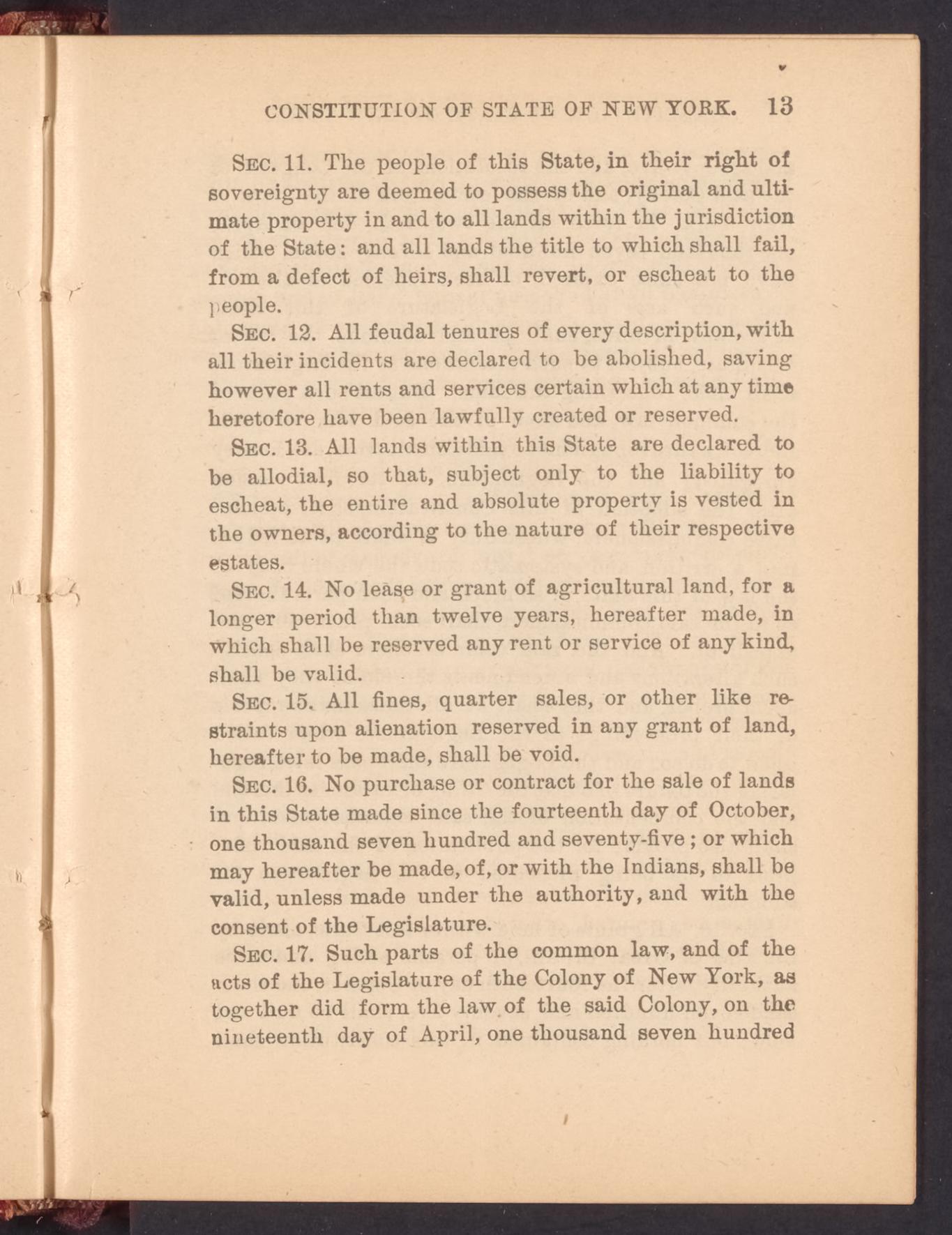

This story is a painful stitch in the fabric of American history. But it also is a story with a moral ending . In 1846, New York passed a new constitution that limited the length of leases to no more than 12 years and broke up the feudal nature of the patroons in the state of New York, which prevented many of the predatory practices that plagued those involved in the Anti-Rent War. Maybe by seeing how the actions of their ancestors made real change in the past, the students of our present can advocate for themselves a better future.

New York. The constitution of the state of New York . Albany, Weed, Parsons and company, printers, 1877. Pdf. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/09034863/>.