Talking about politics is especially popular this time of year. Students and teachers alike are inundated with political topics that are often only fractionally understood. However, in the context of politics, the term "popular" gets a little more complicated.

Popularized by the results of the 2016 election, the debate between popular and electoral has been on the forefront of the political conversation. Despite failing to secure the popular vote, former president Donald Trump did manage to garner the electoral votes necessary to be elected president over his political opponent, Hillary Clinton. Since then, many have been wondering about how the electoral college fits into the scope of democracy. After all, if a larger number of individuals have voted for a candidate, should that not be the candidate that wins? Yet, this scenario is not unprecedented. The 2016 election was the fifth time that a president has won the presidency despite losing the popular vote, a situation which dates back as early as 1824 in the election between John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson. However, as Trump runs for re-election this November, the discussion around the electoral college seems more important and more relevant than ever.

The answer to whether or not the electoral college should be abolished might not be so simple. By delving into the primary sources in the Library of Congress, one can see the context, the benefits, and the pitfalls that the electoral system may hold.

Historical Context

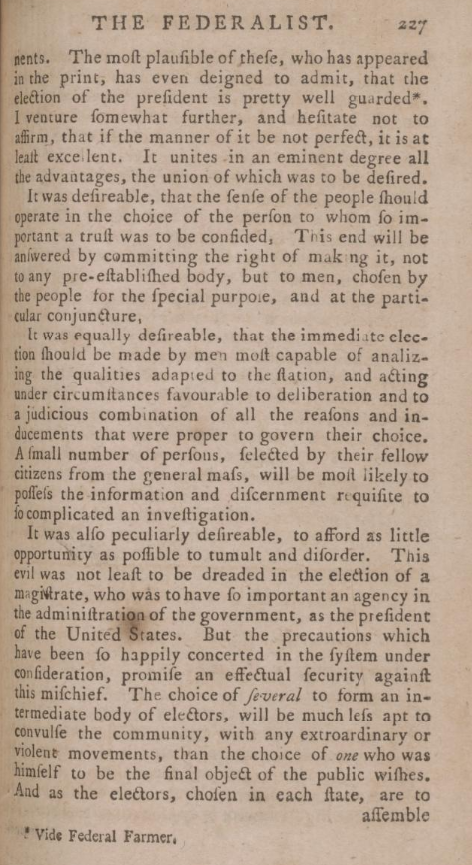

The most important thing to ignite conversation surrounding the electoral college is to have students and learners see how the electoral college has evolved over time. This is an excellent place to use a variety of sources. One excellent source from a name that students will recognize, Alexander Hamilton, speaks about the purpose of the electoral college at the time of its origination, providing an insight into the concerns of the American people at that time. As Hamilton notes, the electors exist as a tool to dissuade "tumult and disorder" among the United States. Through the creation of an electoral body, this ensures that the smaller states (and smaller governments) among the nation retain at least a minor stake in the bid for presidency and are not otherwise overshadowed by their more populous peers. Of course, this means that a popular vote cannot be utilized, but instead must have individuals that represent the stakes of their given populations.

Hamilton, Alexander, James Madison, and John Jay. The Federalist, on the new Constitution . [Hallowell Me. Masters, Smith & co, 1857] Pdf. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/09021557/>.

One notable line from Hamilton’s justifies the selection of these individuals, noting that these electors will be “A small number of persons, selected by their fellow citizens from the general mass, will be most likely to possess the information and discernment requisite to so complicated an investigation.” The idea was that a more educated body would be more apt to represent their populations than any given person pulled off the street. But that itself pulls several questions that can be examined by learners. For example, in a given state:

- Who actually decides on the electors for that state? Does the general population select these electors or are they selected through alternative means?

- Are all electors within a state required to vote the same way, or may some electors vote one way, and others another?

- Are electors partisan, or are they not allegiant to any one political party?

- Is an elector required to vote with the will of the people, or may they make their own democratic decision?

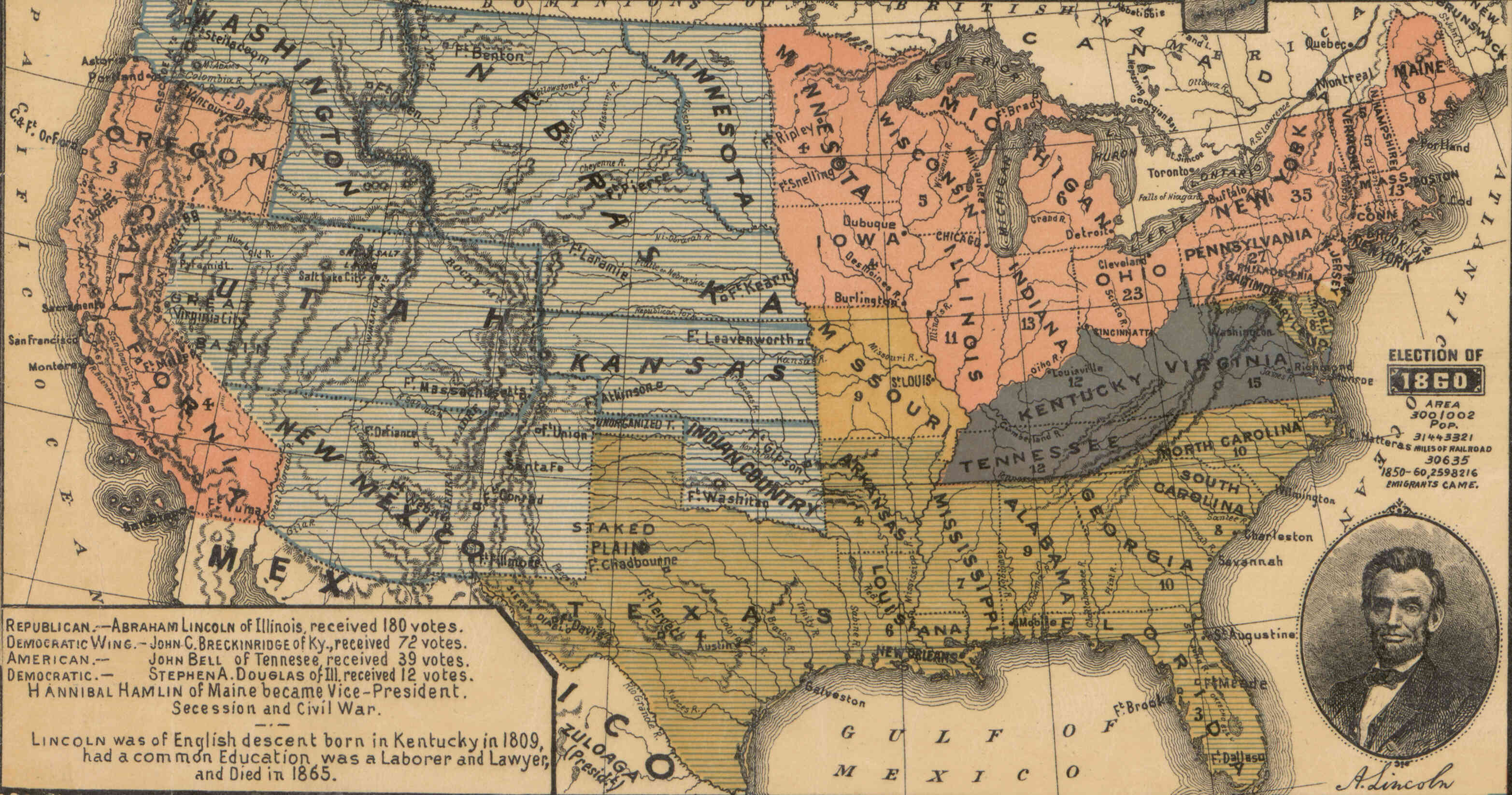

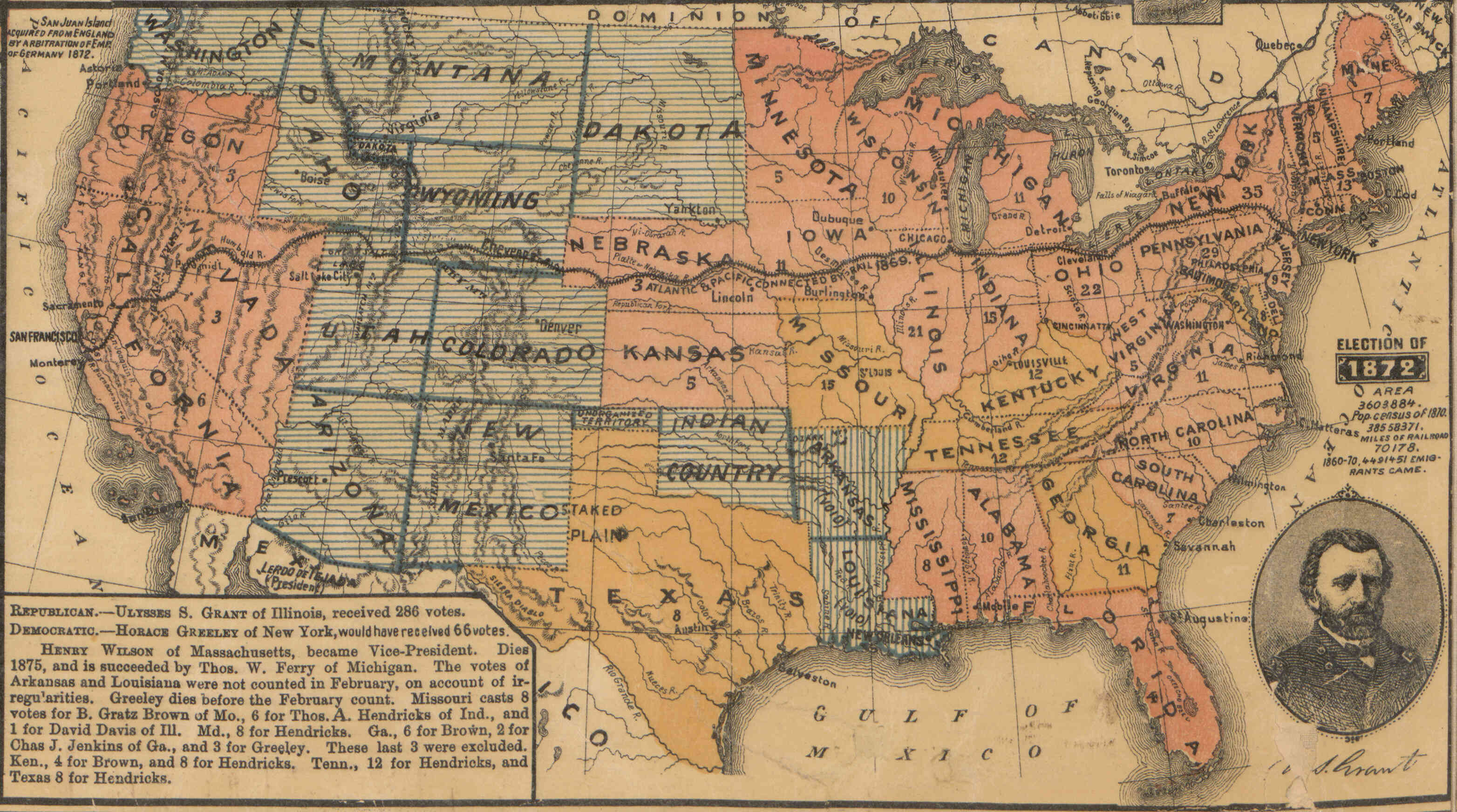

Next, consider using particularly interesting election years to generate discussions about the history of the electoral college in America. Some excellent primary sources are available on this topic, such as the following map:

Donnell, Henry Clay, and Britton & Rey. The presidential elections of the United States . [Washington?: U.S. Election Map Co, 1877] Map. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2012586608/>.

From here, consider breaking the map down into specific election years, ones that have a lot of interesting aspects about them. Split students into groups or stations to have them gradually uncover questions and examine aspects of the electoral college that may not have previously come to mind.

-

A map of the 1824 presidential election

A map of the 1824 presidential election

-

A map of the 1860 presidential election

A map of the 1860 presidential election

-

A map of the 1872 presidential election

A map of the 1872 presidential election

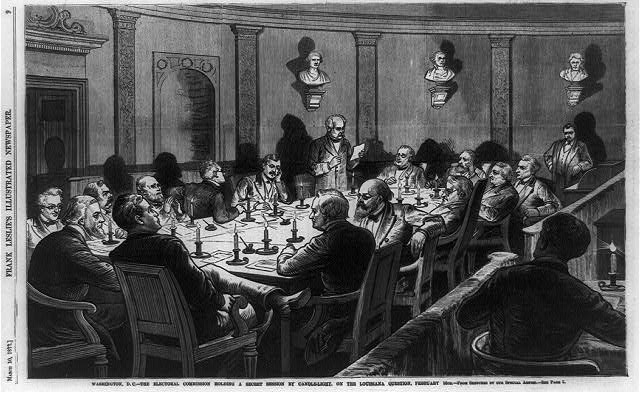

Faithless Electors

It’s important to also teach learners the implications of using an individual to represent the popular vote, as well. Primary sources can be an excellent tool to show what happens when an elector chooses to not represent the interests of their state, sometimes even to the level of collusion! Though faithless electors have never actually affected the results of a presidential outcome, it isn't necessarily without a lack of trying. In 1836, the Virginia electors were pledged to vote for president Van Buren and his running mate, Richard Johnson. However, Johnson's interracial relationship with an enslaved woman caused uproar among the Virginia electors causing all 23 to cast their vice-presidential ballots for William Smith instead. This caused Johnson to be short an electoral vote for majority, requiring the Senate to vote in a contingent election. Countless papers covered this event with their opinion of the electors' actions, including this excerpt from a December issue of the Lynchburg Virginian:

Lynchburg Virginian . (Lynchburg, VA) 26 Dec. 1836, p. 2. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/sn84024649/1836-12-26/ed-1/.

This conversation is especially relevant considering the staggering defections in the 2016 election. In 2016, ten electors of the total 538 voted faithlessly, defecting from their pledged candidate to vote for someone else. Due to state laws which prevented faithless voting, only seven of these defections actually held. While this number might seem small, it actually represents an incredible population of Americans. These seven individuals represented nearly 4.2 million Americans, whose voices ultimately were silenced as a result of this action.

Common Discussion

Recent conversations surrounding the electoral college has given rise to the slogan, “People vote, not land,” which references how not every electoral vote is made equal. Consider the states of Wyoming and California, two of the most widely cited in this discussion. In 2016, California received 55 electoral votes to Wyoming’s mere 3. However, these votes represent populations of 39.15 million and .585 million respectively. This means that, proportionally, a single one of California’s votes is forced to represent nearly half a million people more than a single one of Wyoming’s. What this means is that people in rural states have a higher representative power than those in states with a higher population density. Many believe that it's unfair for one person's vote to be worth more than another - and there certainly is logic to that sentiment!

Henry David Thoreau, -1862, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing right . Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2005685596/>.

But is a majority truly better? Consider the words of esteemed author Henry David Thoreau in his essay "Civil Disobedience" (originally published under the name "A Resistance to Civil Government"), "when the power is once in the hands of the people, a majority are permitted, and for a long period continue, to rule, is not because they are most likely to be in the right, nor because this seems fairest to the minority, but because they are physically the strongest. But a government in which the majority rule in all cases cannot be based on justice, even as far as men understand it." In short, a majority rule does not necessarily mean a just rule. For decades white majority in America brought untold harm to minority groups within the States, yet majority certainly did not make their actions correct. It begs the question:

- Do people in states that have a greater "representation per vote" have certain ideologies or aspects of their lives that must be protected from the majority?

- What would be the long-term implications of removing this "protection?"

So What Does This Mean?

Inevitably, the conversation will move to the following question: “Is the system broken or working as it was intended? If it is broken, what can be done about it?" There are too many considerations for the matter of the electoral college to be a simple discussion - nor should it be. The nature of the college is complex and requires the use of both current situations compared to the environment of the past, necessitating primary sources as a foundation for its study. By having these discussions with students and other learners, the question of “good” or “bad” shifts away from the Electoral College. Instead, it becomes a conversation about the benefit and harm that a system like it can do, and whether or not it’s a system that should truly be supported.