This article was written by TPS Consortium member Meghan Davisson of the Minnesota Historical Society.

Introduction

My work at the Minnesota Historical Society’s Inquiry in the Upper Midwest grant program focuses on developing curriculum and teacher professional development experiences. This spring, my colleague and I designed Empowering Communities with Local History, a cohort program for elementary teachers to teach them how to use hyperlocal history to engage their students in historical inquiry.

We worked with the elementary social studies coordinator at St. Paul Public Schools and recruited about 10 teachers to join us. At our first session, my colleague introduced primary sources and a few strategies of how to find useful local sources online. One of the participants had a wonderful time digging into the Library of Congress online archive to find budget records from the district circa 1902 and the group was able to conclude that indeed, the district has always been deficit spenders.

Our second session traveled across the city to the Hmong Museum where we heard from three community organizations about their work stewarding the history of important subcultures of St. Paul, including Hmong, Dakota, and African American communities. A theme started to emerge in that session about the relationship of our histories with the landscape and the way they are sort of embedded like layers of sediment.

At our third session, we met at the Minnesota History Center, where my colleague and I work, to dig into the archives and see some amazing sources from St. Paul Public School students of the past that had been archived in our collection. We saw a history of the city penned by 1970s 6th graders, apparently tasked with the same call to action as our cohort, and a book of stitched images from kindergartners, which we struggled to believe was created by kindergartners. Let's just say there's more skills lost to obsolescence than just cursive.

For our final session, we met at Historic Fort Snelling at Bdote, where many stories and controversies converge, just like the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers. The teachers presented lessons based on their cohort experiences. They took students on walking tours of their neighborhoods, they investigated Dakota art past and present, they investigated the evolving significance of a Columbus statue on the state capitol grounds, and so much more. In a city and state that has been grappling with our history of settler-colonialism for a long time, with multiple drawn-out controversies over naming and memorials and flags, it was powerful for the teachers to experience these layered stories at sites across the city so they can unpack them with their students.

At our final session, one participant noted that as a new teacher, she had been given a list of online resources for social studies but little direction beyond that. She expressed that this program opened up concrete skills that she was able to put into practice in her curriculum development and classroom right away. Most teachers shared excitement about the local history lens and the connections they made with their students. Every teacher noted the power of visiting local sites relevant to our session topics; it brought the work we did alive. Through this program and our other teacher professional development experiences, we have come to understand that elementary school teachers often do not have the background knowledge and training to locate quality primary sources on their own and incorporate them into their curriculum. As such, this is an area that requires attention and consideration to build those foundations.

How to Find Local Primary Sources

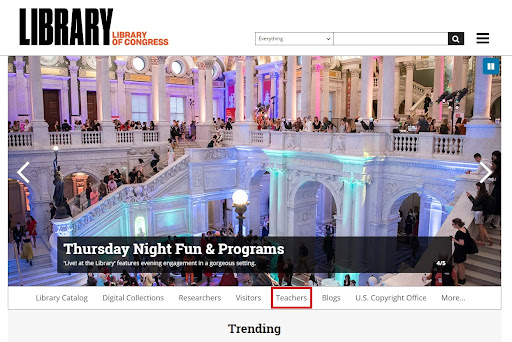

There are a few ways to search for local primary sources through the Library of Congress’ digital collections. The first is through curated materials for teachers. This is a great option if you are new to searching for primary sources and unsure where to begin, or are starting an inquiry into your state’s history. The sources can be used individually, in selected pairings, or as a whole collection.

First, select the “Teachers” tab on the Library home page, then “Classroom Materials.” Then, enter your state in the search box.

A variety of classroom materials related to your state are available, including primary source sets, lesson plans, and presentations. The number available varies by state, but all states have a “Selected Library of Congress Primary Sources” set with a brief Teacher’s Guide, along with additional primary sources. In general, there are few enough results that it is easy to visually determine what fits your needs, but you can further refine your results by classroom material type, topic, era, and recommended grade level.

Alternatively, if you have a topic you are looking for, you can refine your search through keywords and search limits. As we move into August, many Minnesotans are looking forward to the State Fair–known colloquially as the Great Minnesota Get-Together. It is one of the largest state fairs in the country by attendance. For many students–especially in the Twin Cities–this 12-day event (which ends on Labor Day) marks the end of summer and the beginning of the school year. This inspired my next search:

- My initial search for “state fair” yielded an overwhelming 2,695,715 results available online.

- Consider your search terms: you may want to use related terms, or include or drop articles or conjunctions like “the” or “and,” as search results will match all words.

- Time to refine! I find Original Format, Date, and Location to be most helpful in most of my searches. I wanted images, so I selected Original Format Photo, Print, Drawing, and Location Minnesota. This narrowed the search to 17 results–very manageable, so I chose not to narrow by date.

- The results will list locations with the highest results. Click “More Locations,” then “Show: Alphabetically” to easily find your preferred location.

- Part of (Collection), Contributor, and Subject are also useful, especially in large search results. Depending on your needs, you may want to sort your results–for example, by oldest first. Click here for even more search options.

Building a Collection

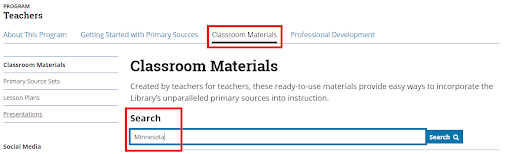

The Minnesota State Fair dates back to 1859, which invites a fun opportunity to practice skills such as comparing and contrasting past and present at the beginning of the school year. Students could compare the panoramic photo to current images of the Fair buildings. How have the Fairgrounds changed over time? The second image is a humorous postcard, and a creative opportunity to test media literacy skills with the exaggerated rooster size. Students could also be prompted to consider the present-day livestock displays. The final photo shows a display of items handcrafted by World War I veterans. Students might note the signs in the display explaining the work and consider its purpose; they also might make comparisons to 4-H projects and art competitions in today’s Fair events.

Hibbard, C. J., Copyright Claimant. Minnesota State Fair . Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2007663373/>.

-

First prize rooster at Minnesota State Fair. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2024689051/>.

-

American Red Cross. Handwork of returned soldiers at the Minnesota State Fair. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2017673624/>.

Take this search for hyperlocal primary sources one step further by following the thread from the Library of Congress Collections to local repositories. For this example, I will take a nationally known event not normally associated with Minnesota–the Civil Rights Movement–and make local connections that students will find relevant to their lives.

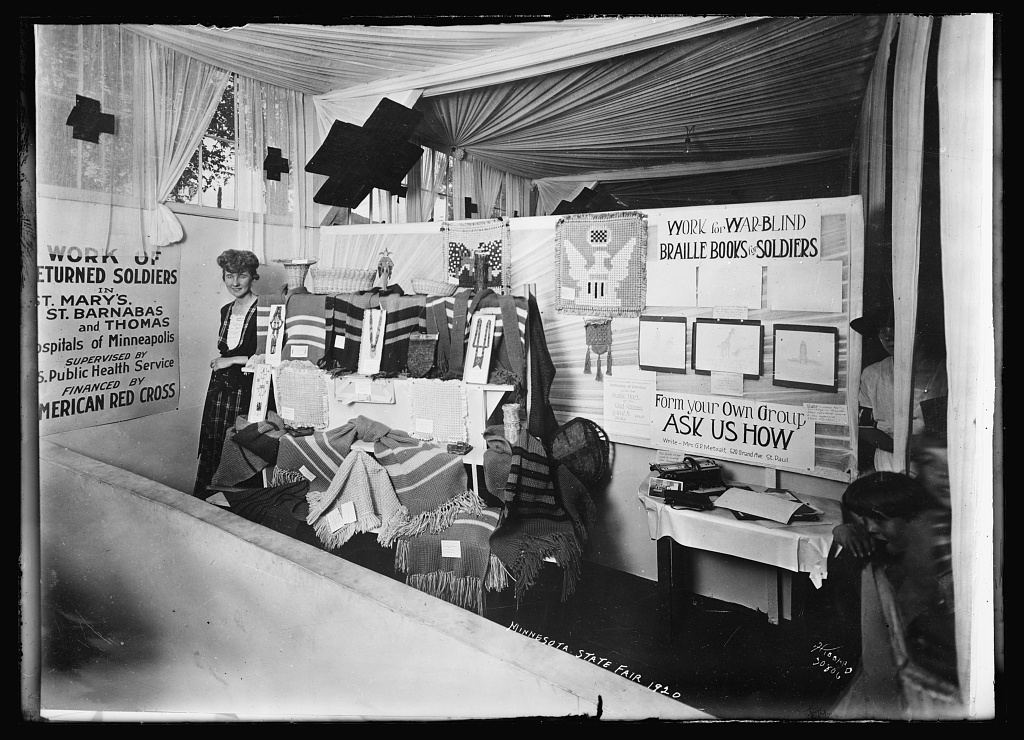

O'Halloran, Thomas J, photographer. Clinton, TN, school integration conflicts. Dec. 4. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2003654360/>.

We started with this image from the Library of Congress (also part of our Youth Movements primary source set). This is an excellent opportunity to use the Library’s Primary Source Analysis Tool, and there is a great deal to see, think, and wonder about in this photograph. Students may notice the crowd, the identities of different people in the crowd, their clothing, their body language and expressions. They may be familiar with the struggles of desegregation during the Civil Rights Movement, including school integration. They may be curious about what people are feeling or saying, and what is happening outside the camera lens. In our context as Minnesotans, students may think of the Civil Rights Movement as something that took place far away, elsewhere in the country. They may not see a personal connection to their place and history here without specific guidance. Unfortunately, a search of the Library of Congress yielded few student-accessible results for the Civil Rights Movement in relation to Minnesota.

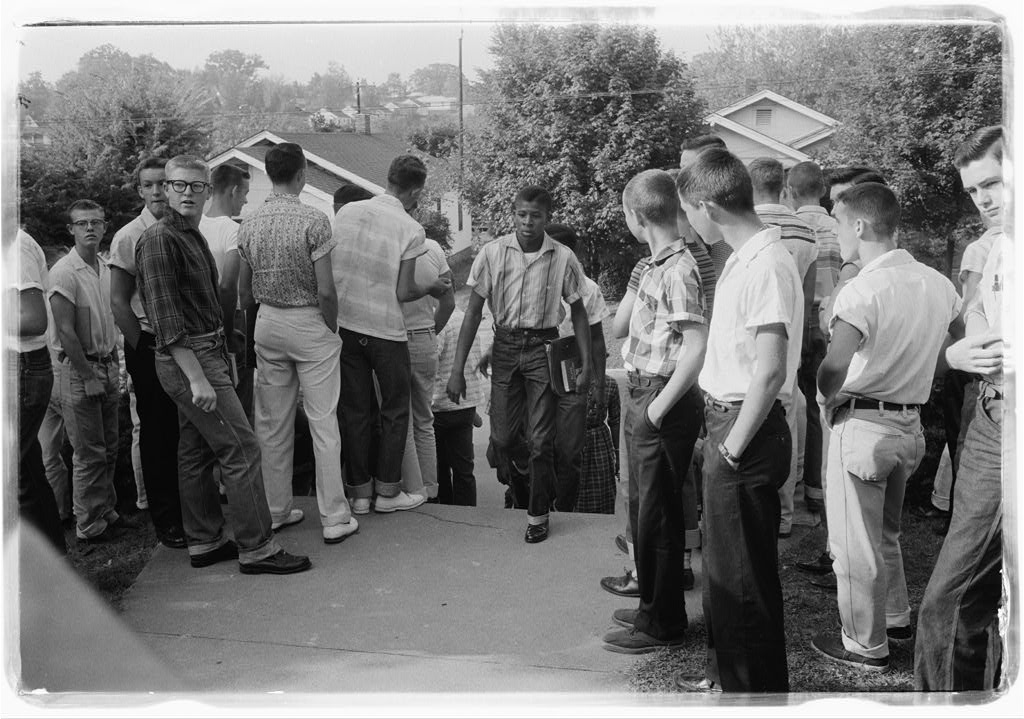

Enter local organizations! Here are two primary source photographs from local repositories that can enrich understanding:

-

St. Paul Dispatch-Pioneer Press, photographer. NAACP members picketing outside Woolworth's for integrated lunch counters, St. Paul. Photograph. Retrieved from the Gale Family Library, <https://collections.mnhs.org/search/collections/record/54c019ae-8019-4836-8f7c-f27865d0175d>

-

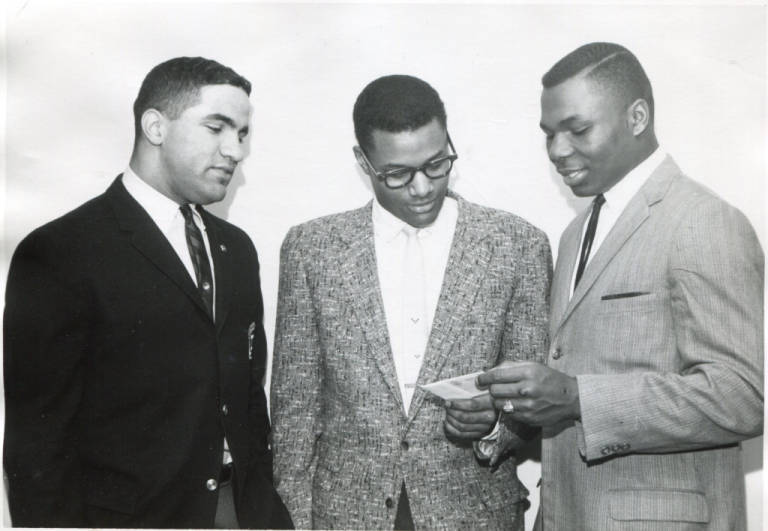

NAACP Youth Group. Photograph. Retrieved from the Hallie Q. Brown Community Center, <https://hqbca.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/hqbca006/id/17/rec/96>

The first is from the Minnesota Historical Society Collections. One way Minnesotans participated in the Civil Rights Movement was through boycotts. Woolworth's lunch counters in Minnesota were integrated, but these NAACP members in St. Paul still picketed to send a message to the company to integrate their stores nationwide. Searching a local community organization, the Hallie Q. Brown Community Archives, allowed us to find the second photo. From left to right, the young men are Sandy Stephens, Ronnie Harris, and Judge Dickson. Light Internet sleuthing suggests all three were football players at the University of Minnesota! Knowing these identities–names, role in the Civil Rights Movement, and role as student athletes–is very humanizing and helps students build historical empathy.

Local connections are exciting; I have seen students light up when they have the opportunity to identify with the past even in simple ways. Highlighting familiar places is one more tool to engage with students and build their understanding of the relevance of history. What local historical societies and community organizations are available to you?

Annotated Resources

- Through the 2022 National Census of History Organizations, the American Association of State and Local History has identified 21,588 organizations across the United States; it is likely that this falls short of the actual number.

- The Minnesota Historical Society maintains a directory of local historical societies and topical organizations. It is possible that your state historical society has a similar list.

- Consider the subcultures that make up your local community, which often maintain cultural centers to support their members and serve the surrounding community. We found that some of these organizations also maintained unique archives and museums.